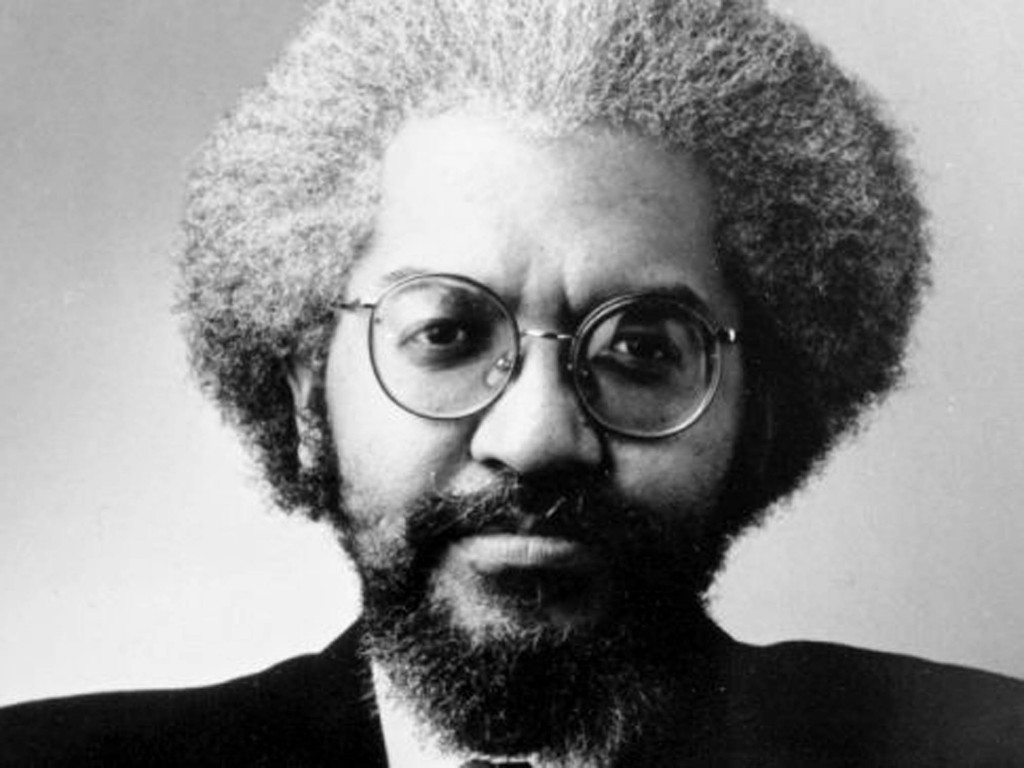

By: Manning Marable

EDITOR’S NOTE: this essay was written on November 12, 2007 and is published posthumously here for the first time.

The recent emergence of Illinois Senator Barack Obama, an African American, as a possible nominee of the Democratic Party for the U.S. presidency, highlights the growing significance of blacks within the upper ranks of the U.S. political system. In the House of Representatives, for example, powerful African Americans include: Congressman Charles B. Rangel of Harlem, the Chair of the Ways and Means Committee, from which all budgetary bills originate; Congressman Elijah E. Cummings of Maryland, the Chair of the Criminal Justice, Drug Policy and Human Resources Subcommittee; Congressman James E. Clyburn of South Carolina, the Democratic Party’s “Majority Whip,” the third highest ranking officer in the House; Congressman Bennie Thompson of Mississippi, the Chair of the Homeland Security Committee; and Congressman John Conyers, Jr., the Chair of the House Judiciary Committee. Blacks are currently mayors of numerous U.S. cities, including Philadelphia (John Street), Detroit (Kwame Kilpatrick), Columbus, Ohio (Michael Coleman), Memphis, Tennessee (Willie W. Herenton), Washington, D.C. (Adrian M. Fenty), New Orleans (C. Ray Nagin), Cleveland (Frank G. Jackson), Atlanta (Shirley Franklin), Cincinnati, Ohio (Mark L. Malloy), and Buffalo, New York (Byron W. Brown).

The “paradox” of this process of black representation within the U.S. state is that the presence of African-American politicians within the government has not resulted in a meaningful advance in the material conditions of most blacks. How and why this has occurred requires a brief review of African-American recent political history.

Back in 1964, the year that the Civil Rights Act was signed, which outlawed racial segregation in public accommodations, the total number of blacks in Congress was five; the total number of African-American mayors of major U.S. cities, towns and even villages was zero; the total of all black officials throughout the United States in 1964 was a paltry 104.

This meant, in practical terms, that the voice of black political leadership largely emanated from two sources: the African-American Christian religious community, such as the Progressive Baptist Convention, and its representatives, including leading Civil Rights clergy like Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Ralph David Abernathy, Wyatt T. Walker, Fred Shuttlesworth and others. Secondly, there was the mainstream Civil Rights community, represented by NAACP national secretary Roy Wilkins, NACCP Legal Defense Fund directory Thurgood Marshall, the Congress of Racial Equality leader James Farmer and Urban League director Whitney Young. These individuals possessed radically different approaches and tactics in their efforts to challenge Jim Crow segregation. But what they all had in common was a strategic understanding about what the fight was about. Few of them entertained any illusions about trying to get themselves elected to Congress. Their goal was the vigorous advocacy of what they perceived to be blacks’ interests, and to use a variety of means – nonviolent demonstrations, economic boycotts, lobbying Congress to pass legislation, etc. – to pressure white leaders and institutions to make meaningful concessions.

The passage of the 1965 Voting’s Rights Act, and the widespread exodus of white racist “Dixiecrats” into the Republican Party, led to the rise of the African-American electorate as a central component within the national Democratic Party. The number of African-American officials soared: from about 1,100 in 1970 t0 3,600 by 1983. The Congressional Black Caucus was formed in 1971 to bring greater leverage within Congress for African-Americans demands. In March 1972, thousands of blacks met in Gary, Indiana, to form a “National Black Political Assembly”, with the explicit idea of constructing a comprehensive, “Black Agenda” of public policy issues that would guide the actions of newly-elected black officials across the country. Some of us involved in the Assembly even anticipated the establishment of an all-Black Independent Political Party, where blacks could exercise the greatest possible freedom in negotiating deals between white parties and institutions.

During the 1980’s and early 1990’s, political events triggered a fundamental transformation in the internal dynamics of black leadership nationally and in the agendas it pursued. First, the rise of a powerful, assertive Congressional Black Caucus largely superseded the political influence of the NAACP and other Civil Rights organizations as the chief formulators of national black public policy. Second, the dramatic electoral campaigns of Harold Washington running successfully for Chicago’s mayor in 1983 and 1987, combined with the Reverend Jesse Jackson’s Rainbow Coalition Presidential campaigns of 1984 and 1988, illustrated that black social protests (aimed chiefly against President Ronald Reagan’s conservative agenda) could use electoral politics as a vehicle for mobilizing masses of people of different races and classes behind a black progressive agenda. Jackson did not win the Democratic Presidential nomination, but his dramatic success in garnering over seven million popular votes in 1988 and in winning numerous primary elections and caucus states proved that a black or Latino presidential candidate could, under the right set of circumstances, win the Democratic Party’s Presidential nomination. Although Jackson was himself a Christian minister, his electoral campaigns shifted the focus of black politics away from the black church and Civil Rights groups firmly into the secular electoral arena. In the quarter century following the Civil Rights Marches of Birmingham, Selma and Memphis, “black politics” had been redefined from economic boycotts, street demonstrations, the establishment of “Freedom Schools,” Septima Clark’s “Citizenship Academies,” and from automobile Black Power-inspired workers creating their own revolutionary union movements in Detroit, to electoral participation within the system.

Demonstrators in the Poor People’s March at Lafayette Park and Connecticut Avenue in Washington, D.C. (June 1968). Source Wikipedia/CC

But the third, and most unexpected political development, was the striking emergence of what can be termed “post-black politics,” or “race-neutral politics.” Prior to the late 1980’s, the vast majority of white American voters, regardless of the party affiliation of ideology, simply would not vote for a black candidate for public office. There existed an “invisible glass ceiling” limiting black upward mobility, within the system, where African-Americans could be elected to Congress, but only so long as their districts contained at least strong pluralities of minorities. Dozens of blacks won election as mayors with cities containing white majorities, but these were nearly always cities containing substantial and highly mobilized black and brown electorates, and traditional allies like liberal unions, Latinos, and women’s organizations.

In the multicultural nineties, as “hip-hop” began to define urban youth culture, and as President William Jefferson Clinton proudly jogged donning a Malcolm “X Cap,” this racial barrier eroded. A new generation of African-American politicians – most of whom were lawyers, corporate executives, city administrators and foundation officers – began to emerge, first in municipal politics and then at the national level. With few exceptions they had no alternative except to advocate the interests of their constituencies – who happened to be white and Latino as well as African-American, middle-class as well as working class, unemployed and poor, those without high school diplomas as well as those with professional and graduate degrees. Michael White, the mayor of Cleveland, Ohio, in the 1990’s was in many ways the archetype for post-black politics; an African-American mayor who was far more comfortable discussing tax abatements and incentives to attract corporate investment to the inner-city, than leading a public protest.

Today, the two most “successful” practitioners of post-black leadership are Illinois Senator Barack Obama, and Newark, New Jersey Mayor Corey Booker. Both men are proudly, assertively self-identified as “black,” as an ethnic identity. But both pursue strategies for public policy change that are not “race-based.” They consciously cater to audiences that are broadly multiracial, and draw the majority of their financial support well outside of the black community. Despite their prominence, they do not play organic roles of interest-group advocacy for all-black groups, partially because their perceived electoral mandate is “color-blind.” The reality of their electoral successes paradoxically limits their ability to advocate on behalf of the specific problems of structural racism that continue to devastate and destroy blacks’ lives.

Within the United States today, a “New Racial Domain” of structural racism has emerged that has undermined the effectiveness of African-American elected officials. This New Racial Domain is different from other earlier forms of racial domination, such as slavery, Jim Crow segregation, and ghettoization, or strict residential segregation, in several critical aspects. These earlier racial formations or domains were grounded or based primarily, if not exclusively, in the political economy of U.S. capitalism. Anti-racist or oppositional movements that blacks, other people of color and white anti-racists built were largely predicated upon the confines or realities of domestic markets and the policies of the U.S. nation-state. Meaningful social reforms such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 were debated almost entirely within the context of America’s expanding, domestic economy, and influenced by Keynesian, welfare state public policies.

The political economy of America’s “New Racial Domain,” by contrast, is driven and largely determined by the forces of transnational capitalism, and the public policies of state neoliberalism. From the vantagepoint of the most oppressed U.S. populations, the New Racial Domain rests on an unholy trinity, or deadly triad, of structural barriers to a decent life. These oppressive structures are mass unemployment, mass incarceration, and mass disfranchisement. Each factor directly feeds and accelerates the others, creating an ever-widening circle of social disadvantage, poverty, and civil death, touching the lives of tens of millions of U.S. people.

The process begins at the point of production. A recent study by Northeastern University’s Center for Labor Market Studies establishes that in 2002, one of every four African-American adult males was unemployed throughout the entire year of 2002. The black male jobless rate was over twice that for white and Latino males. Even these statistics seriously underestimate the real problem, because they don’t factor in the huge number of African-American males in prison or those who are homeless.

For black males without a high school level education, their job prospects are even worse. The Center’s study notes that among black male high school dropouts, 44 percent were unemployed for the entire year of 2002. For black men between the ages of 55 to 64 years, jobless rates for 2002 were almost 42 percent. New York Times columnist Bob Herbert has described these dire statistics as evidence of “an emerging catastrophe – levels of male joblessness that mock the very idea of stable, viable communities. This slow death of the hopes, pride, and well-being of huge numbers of African Americans is going unnoticed by most other Americans and by political leaders of both parties.”

So long as African Americans were the chief casualties in the ranks of those who were permanently unemployed, white elected officials could afford to ignore the crisis. But now, increasingly, millions of white workers who have considered themselves “middle class” are being pushed into the ranks of the jobless. In late July 2004, the Labor Department’s Bureau of Labor Statistics noted that between 2001 and 2003, 8.7 percent of all jobholders in the U.S. were permanently dismissed from their jobs. This figure amounts to 11.4 million men and women age 20 or older. This was, according to the Bureau, the “second fastest rate” of layoffs “on record since 1980.” Among laid-off workers who found new jobs, 56.9 percent were earning less money than from their former employment.

Mass unemployment inevitably feeds mass incarceration. About one-third of all prisoners were unemployed at the time of their arrests, and others averaged less than $20,000 annual incomes in the year prior to their incarceration. When the Attica prison insurrection occurred in upstate New York in 1971, there were only 12,500 prisoners in New York State’s correctional facilities, and about 300,000 prisoners nationwide. By 2001, New York State held over 71,000 women and men in its prisons; nationally, 2.3 million are imprisoned. Today about six million Americans are in prison or jail, on probation, parole or awaiting trial, and roughly one in six Americans now possess a criminal record.

Mandatory-minimum sentencing laws adopted in the 1980s and 1990s in many states stripped judges of their discretionary powers in sentencing, imposing Draconian terms on first-time and non-violent offenders. Parole has been made more restrictive as well, and in 1995 Pell grant subsidies supporting educational programs for prisoners were ended. For those prisoners who are fortunate enough to successfully navigate the criminal justice bureaucracy and emerge from incarceration, they discover that both the federal law and state governments explicitly prohibit the employment of convicted ex-felons in hundreds of vocations. The cycle of unemployment usually starts all over again.

Mass incarceration, of course, breeds mass political disfranchisement. Nearly six million Americans today cannot vote. In six states, former prisoners convicted of a felony lose their voting rights for life. In the majority of states, individuals on parole and probation cannot vote. About 15 percent of all African-American males nationally are either permanently or currently disfranchised. In Mississippi, one-third of all black men are unable to vote for the remainder of their lives.

Even temporary disfranchisement fosters a disruption of civic engagement and involvement in public affairs. This can lead to “civil death,” the destruction of the capacity for collective agency and resistance. This process of depolitization undermines even grassroots, non-electoral-oriented organizing. The deadly triangle of the New Racial Domain constantly and continuously grows unchecked and most black-elected officials seem powerless to challenge it.

Not too far in the distance lies the social consequence of these policies inside the United States: an unequal, two-tiered, uncivil society, characterized by a governing hierarchy of middle- to upper-class “citizens” who own nearly all private property and financial assets, and a vast subaltern of quasi- or subcitizens encumbered beneath the cruel weight of permanent unemployment, discriminatory courts and sentencing procedures, dehumanized prisons, voting disfranchisement, residential segregation, and the elimination of most public services for the poor. The latter group is virtually excluded from any influence in a national public policy. Institutions that once provided space for upward mobility and resistance for working people such as unions have been largely dismantled. Integral to all of this is racism, sometimes openly vicious and unambiguous, but much more frequently presented in race neutral, color-blind language. This is the NRD of domestic apartheid in America.

The terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001, and their political aftermath, have also been pivotal factors that have marginalized black leadership inside the United States. As in previous times of war in the U.S., the vast majority of Americans, regardless of political party affiliation, immediately rallied behind the president after 9/11, demanding military retribution against the Al Qaeda Islamic terrorists. President George W. Bush characterized the “evil-doers” as both “pathological” and “insane,” and for days following the attacks the administration vowed to launch a global “crusade” against Islamic terrorism. To the world’s over one billion Muslims, and to the six million Muslims living within the U.S., the term “crusade” instantly evoked disturbing historical images of the Christian invasions of the Islamic Middle East during the Middle Ages. The Bush administration soon quietly discarded its “crusader” rhetoric, but continued to indirectly promote anti-Islamic and anti-Arab sentiment to mobilize the nation for its “War Against Terrorism.” U.S. military soon invaded and occupied Afghanistan, the nation in which Al Qaeda had established its base of operations under the fundamentalist Taliban regime. Then, in early 2003, U.S. military forces subsequently invaded Iraq, which was accused of harboring Al Qaeda terrorists and possessing “weapons of mass destruction” that represented a threat to U.S. national security.

Like other Americans, African American leaders were morally and politically outraged by Al Qaeda’s terrorist attacks. Yet they were deeply troubled by the immediate groundswell of ultra-patriotic fervor, national chauvinism and numerous acts of violence and harassment targeting individual Muslims and Arab Americans. They recognized that behind this mass upsurgence of American patriotism was xenophobia, ethnic and religious intolerance, that could potentially reinforce traditional white racism against all people of color, particularly themselves. They questioned the Bush administration’s “Patriot Act of 2001” and other legal measures that severely restricted Americans’ civil liberties and privacy rights. For these reasons, many black leaders sought to uphold civil rights and civic liberties, and challenged the U.S. rationale for its military incursions in both Afghanistan, and later Iraq. The pastor of New York City’s Riverside Church, the Reverend James A. Forbes, Jr., proposed that African Americans embrace a critical, “prophetic patriotism. . . . You will hold America to the values of freedom, justice, compassion, equality, respect for all, patience and care for the needy, a world where everyone counts.” Urban League President Hugh Price argued that black Americans must “vigorously support the federal government’s efforts to root out the terrorists wherever they hide around the globe . . .” However, Price also insisted that “black America’s mission, as it has always been, is to fight against the forces of hatred and injustice, to fight for the right of all human beings to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.”

As the U.S. Justice Department began to arrest and hold without trial hundreds of Muslims and Arab Americans, Islamic groups urgently appealed to the Nation of Islam, NAACP and the Congressional Black Caucus for assistance. Approximately 40 percent of the U.S.’s Islamic population is African American, and hundreds of native-born blacks, because of their religious affiliations, also found themselves under surveillance or were arrested, despite having no links to terrorist groups. The Reverend Jesse Jackson openly condemned the police practice of ethnic/religious “profiling,” declaring that the U.S. needed to focus its resources toward the “building of understanding and building a just peace,” instead of resorting to warfare to “root out terrorism.” In March, 2003, when the U.S. military invaded Iraq, a Pew Research Center opinion poll found that only 44 percent of African Americans favored the war. By contrast, white Americans endorsed the invasion by 73 percent, with Latinos favoring military conflict by 66 percent. African-American clergy, led by Brooklyn activist, the Reverend Herbert Daughtry, organized daily “vigils for peace” near the United Nations. The black ministers created a “Martin Luther King, Jr. Peace Now Movement,” which actively participated in the growing anti-war mobilization throughout the U.S.

By early April 2003, the U.S. had successfully toppled the regime of dictator Saddam Hussein, and over one hundred thousand U.S. troops occupied the country. However, the military invasion of an Islamic country strengthened the network of fundamentalist Islamic terrorists, by creating a vivid example of imperialist aggression aimed against the entire Islamic world. In an April 4, 2003, Gallup opinion poll, 78 percent of white Americans supported the military invasion; African-American support for the war had plummeted to only 29 percent.

By early 2004, the Bush administration had begun to aggressively pressure universities to suppress dissent and to curtail traditional academic freedoms. In early March 2004, the U.S. Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control stopped 70 American scientists and physicians from traveling to Cuba to attend an international symposium on “coma and death.” Some of the scholars received warning letters from the Treasury Department, promising severe criminal or civil penalties if they violated the embargo against Cuba. In late 2003, the Treasury Department issued a warning to U.S. publishers that they would have to obtain “special licenses to edit papers” written by scholars and scientific researchers currently living in Cuba, Libya, Iran, or Sudan. All violators, even including the editors and officers of professional associations sponsoring scholarly journals, potentially may be subjected to fines up to $500,000 and prison sentences up to ten years. After widespread criticism, the Treasury Department was forced to moderate its policy.

The long-term catastrophe of the terrorist attacks of November 11, 2001, from the perspective of the Black Freedom Movement, have been two-fold. The U.S. military invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq had greatly eroded domestic civil liberties and civil rights, creating a mass environment of ethnic/religious hostility, permitting indiscriminate police surveillance, racial profiling and arrests. Tens of thousands of young African Americans in the armed forces were stationed in war zones, for a conflict that most blacks strongly opposed. Second, in terms of racial policy, the intense national debate over “black reparations” that had dominated headlines throughout 2001 was derailed, perhaps for decades to come, beneath the tidal waves of ultra-patriotism and American xenophobia. The racial reality was that American state power had partially redefined the “racialized Other” as Arab American, Muslim and/or undocumented immigrant. A “New Racial Domain” was being constructed in twenty-first century America, relegating most blacks, many undocumented immigrants, and other racialized groups to an increasingly marginalized status behind a “color-blind,” racially-neutral regime of mass incarceration, mass unemployment, and political disfranchisement. The national “War On Terror” only reinforced the authoritarian dynamics of intolerance and exclusion that preserved white capitalist power.

Despite official repression, black activist leaders are building resistance in thousands of communities across the United States. In local neighborhoods, people fighting against police brutality, mandatory-minimum sentencing laws, and for prisoners’ rights; in the fight for a living wage, to expand unionization and workers’ rights; in the struggles of working women for day care for their children, health care, public transportation, and decent housing. These practical struggles of daily life are really the core of what constitutes day-to-day resistance for local black leaders.

Manning Marable May 13, 1950 – April 1, 2011