I was a bit taken aback when someone dear to me asked me the obvious when I told her about Ramadan’s arrival last week:

“Why do you fast?”

Before I could answer her, I had to wonder about why I didn’t fast before. I stopped feeling Ramadan when I was 20. I gave up entirely when I was 22, I think. I didn’t care when Ramadan arrived. And when it was over, I didn’t even bother to pray on Eid. Or celebrate it. Slowly, I forgot that Ramadan even existed.

I started feeling Ramadan at a very young age.

I blame my dad’s mom for that.

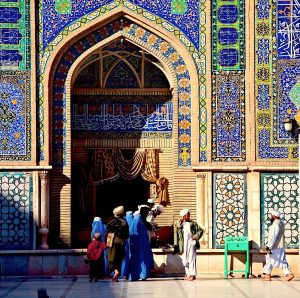

One of my most cherished memories is from when I was five and we lived in Kabul before the war forced us from Afghanistan. My two older siblings and I slept with our two grandmas, grandma, my dad’s mom, and my mother’s mom, who we called ‘unwell’ grandma because for as long as we could remember, she’d been ill.

One of my most cherished memories is from when I was five and we lived in Kabul before the war forced us from Afghanistan. My two older siblings and I slept with our two grandmas, grandma, my dad’s mom, and my mother’s mom, who we called ‘unwell’ grandma because for as long as we could remember, she’d been ill.

There was a war in our country, but Kabul was still safe, yet I was too young to be aware of any of that, safe. Every night, I’d sleep right next to grandma and she against the window. I’d wake up every morning just before dawn to find her reading from her Islamic prayer books. I’d just turn and stare at her lips, as they read the Arabic texts, her wrinkled face illuminated by the moonlight, and I’d drift back to sleep.

She was the source of my religiosity from that time on.

She told my dad to buy me a book called “Qissasul Anbiyaa” (Stories of the Prophets) when I was six and she taught me how to read so I could learn about our heritage. She was the one I came to when I wanted to learn how to pray. She taught me how to correctly pronounce the Quran’s Arabic text because even though we were proud Arabs – she never failed to remind me -, we’d forgotten our native tongue and spoke Farsi after years of living in non-Arab lands. I remember the first time I memorized Surah Ikhlas, she was glowing with pride. And then when I was 7, she taught me about Ramadan.

I didn’t know then, but she was preparing me. I was her little soldier who’d grow up and fight for love like the Mujahideen fighting the Soviets in Afghanistan, she told me.

I once asked her why they fought and why we’d left for Pakistan. “They love us, so they die because that will bring peace and we could go back home,” she said. When we lived in Kabul, she’d hide our Mujahideen relatives in our house when they came to visit. Then I was too young to understand and kept complaining about the “rebels” in our home and she’d get furious. I guess she took it upon herself to make me understand because she loved me.

Part of that understanding was Ramadan. I have read so many reasons about why fasting is good. “It makes you one with the rest of the Ummah,” or “It is the most blessed thirty days of the year,” or my favorite, “It will forgive your sins!”

The reason I started observing Ramadan was far simpler. I fasted because I was my grandma’s little soldier. I wanted her to be proud. And when I complained about feeling hungry the first time I attempted to fast, she smiled and said, “You are only 9. You can iftar at lunch.” She was with us only for one more Ramadan, though. She died after a protracted and excruciatingly painful battle with tuberculosis.

Like ‘unwell’ grandma, her lungs gave up, too.

I remember sitting next to her as she lay on her death bed. I wonder if she saw my lips reciting Arabic prayers as her soul departed. I remember walking to the graveyard with everyone next morning. Too young to shoulder her coffin, they let me help in lowering her into the grave. Grandma’s little soldier… I poured some earth over the stone slabs that hid us from me forever. Then, I left with the other men as they talked about the Mujahideen, they sounded excited as their victory was near.

I never saw my dad cry over it. Neither did I shed any tears. I don’t even remember explaining anything to myself. I was a ten year old who firmly believed that his grandma was in heaven and from there, for years, she kept watching me fast. She saw me fasting the entire month a year later. A couple of years passed and I hadn’t just fasted, I’d gone to the mosque to pray taraweeh. And the train of my life’s movie kept marching… But unlike Bollywood’s cinematic creations, I didn’t grow up to be who I was when I was a kid. Sort of like the Mujahideen, who’d started out ready to die for us and were now killing whoever was left behind, destroying most of our country in their wake.

My dad gave up on them first. I gave up a while later.

They weren’t the only disappointments that growing up brought me.

I gave up on people to automatically stand for justice. I gave up on the strong to stop oppressing the weak on their own. For the weak to stop oppressing the weaker once they were liberated. I saw hopelessness in the eyes of children and fatigue in the faces of their fathers who couldn’t feed them. I saw sickly women sitting under the open skies, burning under the scorching sun of Peshawar, begging. People in tents, people on the street, people on the buses… suffering, unimaginable suffering, all too much for the little soldier and I thought, “God, I hope you can take care of my grandma because you’re not taking care of these people.”

And after a while, I gave up on saying that too.

But while I gave up on many things, I never gave up on love and I never gave up on my grandma. Her kindness. Her wrinkled face. Her unrelenting belief that one day, I’d grow up to be someone she’d really be proud of: her little soldier. The only thing more difficult than growing up, is journalism focusing on human rights. Between listening to people’s horror stories and writing them down, there’s precious little time left for the living; the dead can wait when I die, I thought.

But last year when I realized that it would be hard for me to ever visit her grave again – not that I’d been there in 7 years – it was just before Ramadan. The thought of never being able to stand near her grave, read Ikhlas thrice and Fatiha once suddenly  became unbearable. And I thought, maybe I should fast. It came out of the blue. I’m by no means a conventional Muslim anymore. Neither are my views on the divine nature of the universe itself, my lack of belief in a heaven or hell, my support for LGBT rights or female choice in all matters. Most of all, my rejection in any obligation to observe orthodox religious practices like praying or observing Ramadan make it sound a bit weird for anyone to think I’d fast.

became unbearable. And I thought, maybe I should fast. It came out of the blue. I’m by no means a conventional Muslim anymore. Neither are my views on the divine nature of the universe itself, my lack of belief in a heaven or hell, my support for LGBT rights or female choice in all matters. Most of all, my rejection in any obligation to observe orthodox religious practices like praying or observing Ramadan make it sound a bit weird for anyone to think I’d fast.

But fast I did.

And after years, I actually felt it. I looked at the clock a maximum of twice or thrice a day – miracle, I know. I remember once I was working and 30 minutes after iftar time, I went to the kitchen to cook a meal to finally eat and only then did I realize that I could’ve at least drank water. But I didn’t feel thirst.

That experience was magical. This year, I want to repeat it. Not because I’m trying to please a deity who requires anything from me to be pleased, but because I know that the love my grandma taught me about permeates throughout the universe. That love helps me get up each morning and start the uphill battle for justice that I know I’m almost certain I will lose. It helps me carry on today even though I gave up yesterday. Maybe there’s no hope, but there’s always that love.

And somewhere far away, beyond the eternal dark night of the cosmos, beyond the light of the moon, my grandma is still watching her little soldier who isn’t little, but still carries on fighting. And as long as I keep fasting in Ramadan, maybe when it’s all over and there is no more love left, and I, too, am lowered into a grave with slabs of rock over me, I hope to wake up to see her wrinkled face again and stare at her moving lips until I fall back to sleep.