My little brother, a freshman in high school, recently texted me, “I just had history class where we talked about what we know of Islam. I was so scared that someone would say something racist. My hands were shaking. Everyone acted like they knew what they were saying … I was the only Muslim in the room.”

I felt helpless when I saw this, wishing I could shield him from these lessons in American socialization and racialization that politicize, undermine and demonize the religion that we preferred to experience as our mother’s nagging. As his classmates boiled down 1,400 years of Islamic civilization to an ill-informed discussion of jihad, I felt his dread and anxiety as my own. Having grown up in post-9/11 New York City, I immediately remembered my own racing heartbeat and clammy hands, and the wariness that overcame me whenever “Islamic terrorism” was discussed in my classes.

Meanwhile, as President George W. Bush’s war on terror led to America invading one Muslim-majority country after another, I was grouped in with the endless media depictions of shrouded, presumably Arab and oppressed, women abroad. This had less to do with me than the prevailing assumption of Islam’s homogeneity, and its conflation with radicalism, misogyny and terrorism.

The 2016 election outcome has been nothing short of stunning. The days after Donald Trump took office have witnessed numerous hate crimes by his gloating supporters, KKK rallies, and thousands-strong anti-Trump protests in major cities. Hostility toward Muslims, among others, has been consistently perpetrated by the president since the traumatic campaign season.

The Trump administration, knee-deep in xenophobic and hyper-capitalistic White nationalism, has formalized the tenuous place Muslims have long held in the American political imagination as a national security problem

In the midst of the ongoing normalization of an extremist who falsely claimed that Muslims celebrated during 9/11, proposed the large-scale entry of Muslims into a national registry and is barring Muslims from entering the country, I find myself nostalgic for Bush’s semi-coded racism.

While toxic Republican rhetoric and full-blown complicity in the Trump administration has been especially hurtful and harmful, policies implemented by both parties have contributed to the current climate. Post-9/11 America oversaw the increased surveillance of Muslim communities; discriminatory registration into the National Security Entry-Exit Registration System (NSEERS) of more than 80,000 Muslim men, subject to interrogation, detainment and deportation; greater harassment by security and police forces; the consistent political relegation of Muslims as meaningful primarily on the front line against homegrown terrorism.

Still, Dr. Wahiba Abu-Ras of Adelphi University characterizes Bush-era Islamophobia as mere microagressions compared with the macroagressions of the Trump-era. The FBI recently reported a 67% increase in anti-Muslim hate crimes in 2015 since the previous year. This acceleration of violent hate crimes has been brutally felt in my hometown of Queens, where an Imam and his associate were gunned down in front of their mosque.

The Trump administration, knee-deep in xenophobic and hyper-capitalistic White nationalism, has formalized the tenuous place Muslims have long held in the American political imagination as a national security problem. Trump’s first 45 days made good on his 100-day plan to “restore national security,” which listed a “Muslim ban” in the same line-item as promises to expand military investment. The conflation of Islam with terrorism has horrific implications for public safety and has gone hand-in-hand with the mainstreaming of bigotry and the concealment of White supremacist violence, as the media and government fail to label atrocities committed by White men as acts of homegrown terrorism. Trump has ushered in an age of revitalized White supremacy, where his name is scrawled in Muslim spaces as a way to denigrate and intimidate the community.

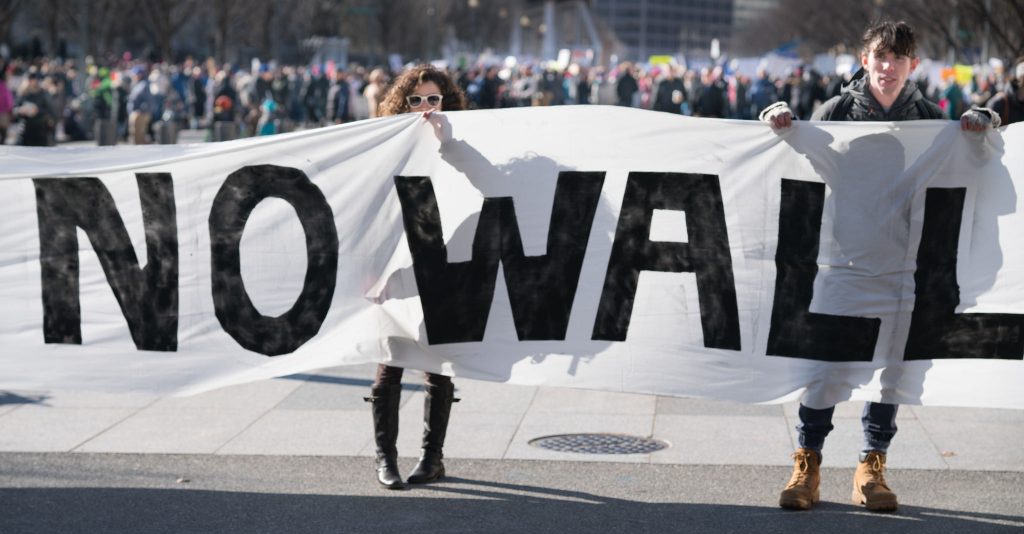

A protest in Washington in February. Flickr/ Victoria Pickering.

Trump’s inadequate response to nationwide hate crimes, including the desecration of Jewish cemeteries and vandalism of mosques, belittles the humanity and pain of these communities. It is not surprising, however, in light of his administration’s aversion to complexity and facts as it moves forward with bans, walls and militarized violence targeting Black and Brown bodies. Trump’s false assurances of security to his supporters serves doubly as a crucial reminder of who the Other is, while actively constraining notions of American citizenship.

Researchers use the term “minority stress” to reflect on the lived experiences of marginalization shared by minority communities. For Muslims, and many non-Muslims assumed to be Muslims, this includes fear of attack and the forced compartmentalization of our presumably antithetical identities as Muslims and Americans. Since 9/11, numerous studies have noted Islamophobia’s impact on mental health among the American Muslim population, most notably among Arab Americans as evidenced by higher levels of anxiety, depression and PTSD relative to other minority groups. Researchers have cited causes including racial profiling, discrimination and feelings of danger.

Now, more than ever, the public health field must reaffirm its commitment to health equity and create pathways for political action and resistance that protect our most vulnerable communities

The effects of chronic stress on health are well-documented — trauma is embedded within individual bodies as higher allostatic load, or physiological “wear and tear,” leading to an increased risk of cardiovascular disease. Even more troubling, research has shown that chronic stress can result in epigenetic changes, or alteration of our DNA; these “molecular scars” can then be passed down to future generations.

Furthermore, American Muslims are comprised of a relatively large immigrant population, with an internalized stigma toward mental health issues. Numerous studies have associated discriminatory experiences within the health care system and adverse health outcomes among those who look identifiably Muslim. Perceived stigma can pre-emptively bar individuals from accessing healthcare. An Islamophobic environment heightens the risk of greater disparities in health, particularly in accessing mental healthcare.

Black Lives Matter protest. Photo via Jocelyn Chuang.

In light of this growing public health crisis, the position of medical and public health officials, enacted through an explicit human rights framework, should be one of moral opposition to an agenda that fails at any semblance of justice and instead furthers the tangible deterioration in health of entire communities. The provision of care is political, whether it is achieved through public health efforts, medicine or the invigoration of civil society. I take strength in remembering the organizing power of NYC’s immigrant and Muslim communities and allies to resist the unconstitutional surveillance of our neighborhoods and NSEERS after 9/11. Public health professionals should heed lessons of creative resistance, to reimagine form, scope and stakes of care giving. Now, more than ever, the public health field must reaffirm its commitment to health equity and create pathways for political action and resistance that protect our most vulnerable communities.

U.S. history can attest that this fight for inclusion and demand for the full realization of rights to citizenship, while being barred from it at the highest levels, is a very American phenomenon. I’m reminded of author Junot Diaz’s blessings: “Radical hope is our best weapon against despair, even when despair seems justifiable; it makes the survival of the end of your world possible. Only radical hope could have imagined people like us into existence. And I believe that it will help us create a better, more loving future.”

After the election, my little brother asked me how he could volunteer for his local assemblywoman as a way to learn about his community’s issues and political institutions. What else does a 14-year-old American Muslim boy’s desire to immerse himself in political action in this moment inspire, if not radical hope?

*Image: A Black Lives Matter protest. Jocelyn Chuang.