Scholars, academics and even great Roman philosophers have discussed the power of the visual image. In the context of news and social consciousness, images have changed the way in which society has come to view the world and itself within that world. As new technologies have emerged —allowing for the editing and doctoring of photography, both still and moving —so too have ethical concerns.

David D. Perlmutter, dean of the College of Media and Communication at Texas Tech University, writes in Image Ethics in the Digital Age that recent television commercials featuring Fred Astaire and John Wayne peddling products are “but preliminary sketches of a fantasy reality to come where the working life is not arrested by death; indeed, death may be, in the language of Hollywood, a ‘smart career move.’”

While CGI is commonplace in Hollywood today, and the recycling, alteration and manipulation of footage has allowed for actors to appear in situations, movies and places where they had not previously been, the use of the deceased to provide continuity to a character to which fans are either deeply connected or the story is dependent has created a stirring ethical debate.

Peter Cushing, perhaps better known for his iconic role as Grand Moff Tarkin in the original Star Wars movie,was digitally reanimated into the new Star Wars movie, Rogue One, some 20-plus years after his death.

To bring Cushing back, Guy Henry performed as Tarkin while cameras rolled. In post-production, he was digitally altered to appear as Cushing. Preexisting footage (largely from Cushing’s work on A New Hope) was used to make the transformation believable.

The recent death of Carrie Fisher prompted discussion of the possibility of her resurrection in Star Wars Episode Nine, but a recent statement from Kathleen Kennedy, head of Lucas Films, confirmed that Fisher would not be posthumously digitally inserted in the franchise she helped launch into the upper echelon of cinematic achievement.

While family members may be eager to see their loved ones back on screen in strong and empowering roles, debates regarding the true desires of the individuals abound. No matter how close a family member is to the deceased, to what degree can the family responsibly dictate the desire of the individual to continue to be alive for the silver screen? If the actor’s character or even public persona is placed in a situation the actor would not have approved of, they are still solidly placed within that narrative and etched into the annals of cinematic memory, with no opportunity for recourse or defense. When it comes to movies like Star Wars, it might be more accurate to say that they are enthroned in a sacred space within an international cultural psyche.

Carrie Fisher as Princess Leia >Flickr/Tom Simpson

If images, real or fictional, truly do define the way in which we see ourselves and others, the unwilling insertion of the dead in the world of the living may be ushering in a new type of zombie obsession in Hollywood. The high-tech puppetry by which Hollywood is able to resurrect is both inspiring and horrifying. At the very least, it is a little unnerving.

The advent of formidable CGI animation has created discussion of technology putting flesh-and-blood actors out of work. Now, it seems as though actors will have to decide if they want such technology to keep their likeness working long after their death.

Perhaps what is more diabolical about such technology is not simply its ability to reanimate the dead, but that it can give the dead lives that they never lived. Inserting individuals into commercials, movies and campaigns of which they were never a part or approved (think Fred Astaire and John Wayne), has altered their personal narratives. They now exist, in the public consciousness, in a time and place in which they never truly were. They have participated in a story they never read. While some may cry “homage,” others may decry the appropriation of a life lived.

The death of a fictional character is the choice of the writer, and fans must accept the loss. When a very real actor, who portrays that character, dies, the writers still have a choice and fans need not worry they may never see that character again. Perhaps, movies, like television,are in a perpetual state of day, never requiring or accepting the finality of the reality in which they play. As post-modern theorist Jean Baudrillard suggests in Cool Memories II, these mediums embody “our fear of the dark, of night, of the other side of things.” There is no need for the shadowy finality of real-world death when technology possesses the ability to resurrect not only characters, but the individuals who portrayed them.

Prior to these advances in CGI technology, this law was largely concerned with the use of images to sell merchandise or for the procurement of financial gain. Now, similar discussions surround the use of these images in visual and audio mediums.

Unsurprisingly, California has been a key player in the movement to protect the right to control how an actor’s image is used after death. A 1984 law established postmortem rights of publicity, at least until 50 years after the death of the actor. This has since been extended to 70 years.

These protections, while available in California, are not available everywhere. For example, the United Kingdom has no such protection, and though Lucas Film requested permission from Cushing’s estate, it was under no legal obligation to do so.

Robin Williams, prior to his death, signed a deed preventing the use of his image or likeness for 25 years after his death.

Debates between the estate, family and producers is sometimes compounded by the devotion of fans who feel either unprepared to let go of a character because of the death of its actor, or who would rather not see another actor fill the iconic role of a favorite thespian.

When producers of IP3, a franchise that prominently starred Bruce Lee, sought to include him in the third installment of his film, they faced lawsuit threats from Lee’s estate. Though producers were working with Lee’s brother, Bruce Lee Enterprises said in a statement that the filmmakers would be violating copyright laws if they continued with their plan to incorporate a digital Lee.

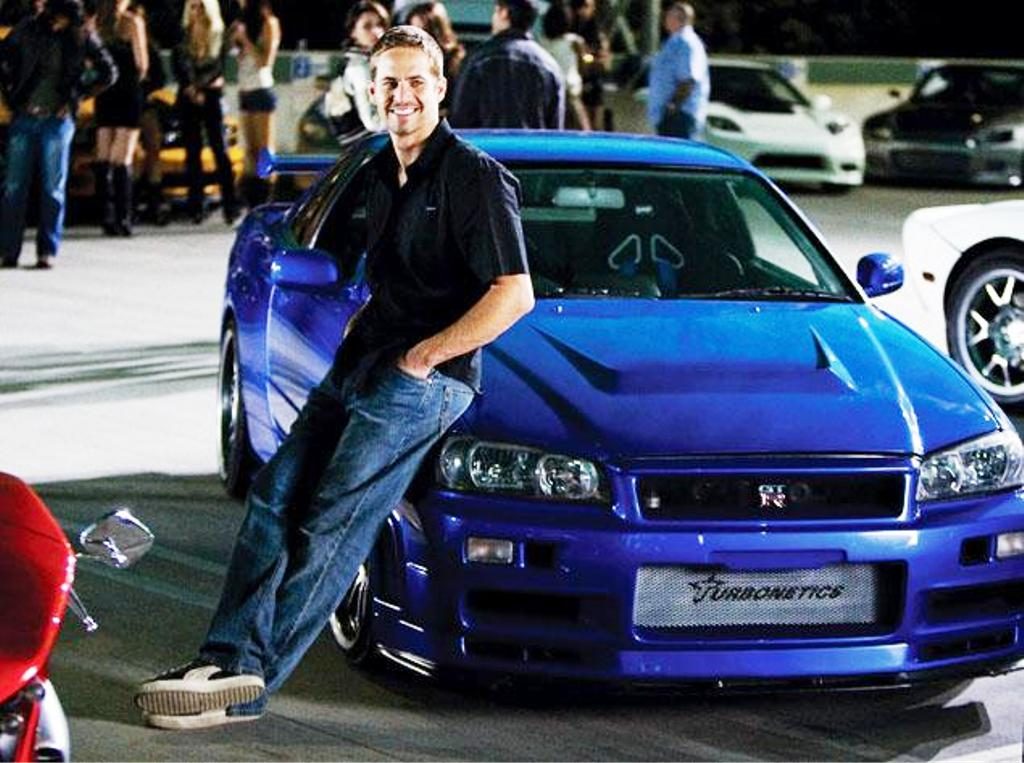

In the case of Fast and Furious 7, the sudden death of Paul Walker before his scenes could be completed left a gaping void in the film’s narrative that threatened the stability of the story line. Walker’s character had a large role in the film and series. To complete the film, Walker’s brothers served as stand-ins for his remaining scenes. In post-production, their images were altered to appear more like Walker.

Paul Walker in the original Fast and Furious >Flickr/DFireCop

The end of the movie paid special tribute to the actor using his brothers and CGI magic. This served as closure of the character’s story line and was a farewell to the actor for whom fans had built a connection throughout the series.

The ability to use deceased actors to continue movie franchises may prevent the seemingly continuous rebooting that has become a Hollywood staple. Instead of creating new movies, new roles and filling them with new actors, the opportunity to resurrect popular and high-grossing actors from the grave may help Hollywood profit even more off of today’s nostalgia-driven consumer, thus continuing to bolster billion-dollar franchises without losing audiences who might otherwise feel disconnected by new actors in iconic roles.

Debates aside, technology has a way of dictating, or at the very least directing, future practices and priorities for society. Sagas and those who exist within them are not easily forgotten, even in death. The ability to preserve images, moving and still, and weave them into legend is admirable in the context of capturing a moment in time. Now, it seems, we may venture down the path not of preservation, but of resurrection and that path is, at least now, lined with ethical tripwires. Perhaps more actors, whose careers have been dependent on their ability to breathe life into their characters on screen, will need to start signing “Do Not Reanimate” directives.

*Image: Zombie paper silhouettes >Flickr/Gabriel Garcia Marengo.