Growing up in an interracial household during the turbulent 1960s and ’70s in Crown Heights Brooklyn left me with a mixture of dread and ambiguity with respect to self-identity. Owning the distinction of being called “high-yellow” and a curly haired Jew in the same lifetime, I often stared in the mirror for long stretches of time trying to figure “me” out. The Black girls in my building at the intersection of Sterling and Kingston ran their fingers through those same curls and wished they had white hair like mine. Years later in Lefferts Junior High School, I longed for the nap so I could grow a ‘fro like my cool classmates.

My parents met through the American Communist Party, which embraced mixed-race dating. This is not meant to demean as doctrinaire the love and affection between my folks that endured more than 56 years, but to emphasize that they were hardcore radicals to the bone, unafraid to thumb their noses at societal norms despite what people may think.

When they married in 1947, New York was an exception to the 31 states with anti-mixed-marriage laws on the books. Forged in the crucible of racism and anti-communist fervor, the bond between my parents was so strong that my mother nearly died from the stress caused by her daily visits to my father, who no longer remembered her when he mercifully succumbed to Alzheimer’s in 2003.

The author’s mother and father at a Rosh Hashanah celebration at the Cobble Hill Nursing Home in Brooklyn in 2000

We were beset by turmoil and struggled to make ends meet during the McCarthy witch hunts. My home life included playing chess at an early age with my siblings — I wish I could find the yellowed newspaper photo my mother cherished of my two older brothers and I playing chess with her in Brower Park on a board for four players she made from oak tag.

It was not until reading the Quran while serving in the Coast Guard that I sensed a safe haven

In between spurning powdered milk and fighting for who would get the last lamb chop, raucous arguments were the norm at the dinner table. “Jump in the pit and match the wit,” my father would say, as we learned to argue both sides of the equation.

Some of the most interesting banter emerged from the international guests my father brought home when he worked at the United Nations. They came from all over: Nigeria, Egypt, Israel, the West Indies and England. After imbibing liberal doses of alcohol, their lively conversations never failed to stimulate the intellect nor increase my vocabulary of colorful words.

The bookshelves in our apartment reflected the free range of ideas and love of learning unencumbered by censorship or dogma. On any given day, I could read about genitalia in Masters and Johnson, the genesis of Marx’s dialectical materialism, or guerilla warfare in Vietnam. I became fascinated by the New Testament, which I eagerly scanned for the words in red that denoted Jesus’ actual speech.

But it was not until reading the Quran while serving in the Coast Guard that I sensed a safe haven. I was drawn to a religious text that asserted there could be no compulsion in religion, that the distinctions between religions should be measured by actions rather than empty naming, and that all beings received their color from Allah — and who could be better than Allah at coloring? In the Quran, all words could be colored red as the immutable word of God.

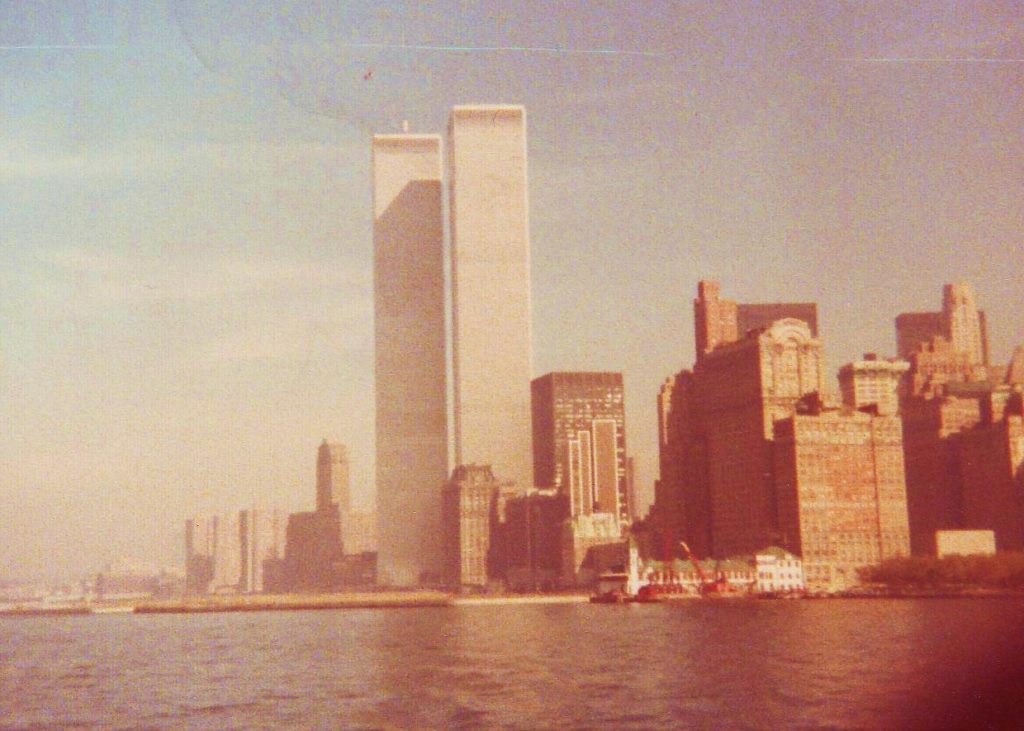

In my heart I envied the force and power of the Quran, how phrases resonated in my head, how a particular recitation or call to prayer could raise goose bumps on my arms, a lump in my throat, sometimes even moisture to my eyes. But the self-identity I had painstakingly built brick by brick around the Quran with the capstone of Prophet Muhammad collapsed after 9/11. Like the gravity that flattened the Tower floors, the presuppositions resonating within my cephalic echo chamber fell beneath the cumulative weight of question after question imploding one upon the other.

The World Trade Center in the 1970s >FLICKR/Mr.TinDC

The once visceral appeal of Islam as a refuge from identity politics now appeared as a spider’s web, a fragile mirage that offered me temporary shelter within the comfort of illusion. After what seemed like a lifetime endeavor for esteem and location, I found myself staring into a dark mirror once more, reflecting on who I was and how people saw me.

Yet the coup de grace to my worldview came with a brush with imminent death several years after 9/11. Unlike the intoxication of hypoxia in a near-death experience, for an instant that seemed like an eternity, my mind raced before the abyss that only moments ago served as my mirror. Life seemed but a flash of images where what appeared to be my last thought became the only truth frozen in time that mattered.

I had been photographing an event in the rotunda of City Hall when out of nowhere, shots rang out from the council chambers next door. A disgruntled gunman had just killed a recently elected City Council member and was in turn shot to death by a quick-thinking police officer.

But the actual circumstances were secondary to the stark image of solitary death they distilled. Etched in the tunnel vision born of fear and adrenaline, I thought, this is it, this is how my life ends. Combined with 9/11 and a career investigating fatal fires, an insufferable hole tore through the core of my being, a deconstruction ended, a reconstruction commissioned. Everything I had ever been told, everything I had ever read, all my dreams, hopes and fears seemed like so much bull manure in an instant.

But from the manure came more: a fecundity that nurtured the discovery of my own voice for reconciling disparate elements within and without. Writing proved cathartic, albeit painstaking and laborious. It was not so much the facticity of events but the plurality of connections I could infer from them. Like chipping paint on a Coast Guard Cutter to expose bare metal, writing enabled me to reveal stratified undercoats and then color them anew with fresh understandings.

Sifting through the Ashes

In rehashing 9/11 for the nth time, I recently recalled a scene at a makeshift fire marshal field unit in a public school near Ground Zero. The supervising fire marshal who mentored me at Bronx Base was there, covered in white dust from head to toe, so much so that you could not tell he was Black. Despite the dire circumstances, I had to stifle a laugh because he appeared like a caricature of Al Jolson in whiteface.

Remembering him reconnected me to an incident in the Bronx that occurred shortly after I was promoted to supervisor. Both he and I were on duty a few weeks before Christmas when a middle-aged Black man entered the base to inquire about fire exit compliance. I vaguely recall him mentioning that he was part of an ongoing protest against Freddy’s Fashion Mart, a White-owned clothing store on 125th Street in Harlem that wanted to expand next door to a popular Black-owned record shop. We explained our role as fire investigators and told him how to file a complaint with the Bureau of Fire Prevention for any alleged fire safety violations.

Christmas in New York City >Flickr/thenalls

Our conversation digressed and he commented that he was proud to see two “brothers” with rank in the Fire Department. That made my day, not only because I was in the top five of the promotion list with two other Black and Hispanic fire marshals, but also because he recognized me as Black! My elation turned to horror however, when I realized he was the same person who shot and killed several people at Freddy’s later in the week, then turned the gun on himself after setting a multiple-alarm fire.

I tried to imagine what fueled the rage that would drive someone to fly a plane into a building, murder an elected official in cold blood or shoot innocent Christmas shoppers point-blank before turning the gun on himself. Having spent most of my career looking for answers in ash and rubble, I reflexively reconstructed the major events in my life to extract meaning.

Rage, Ressentiment and the Differend

I went back to my experiences at Stuyvesant High School in New York City. The coursework was extraordinarily demanding and I floundered my first year. Most of the students were either White or Asian, and I came to resent how easy it all seemed to come to them. My social awkwardness didn’t help either, as I often felt like a third wheel in their conversations. Then, the subway ride on the A train from Nostrand Avenue was sheer torture, after which I had to change at 14th Street for the LL. The trains were always packed, air conditioning non-existent, and on more than one occasion, I had to get off the train for fear of throwing up in what felt like stifling sardine cans.

Playing varsity sports on the football and handball teams helped me to adjust finally, but after one semester, I wanted to transfer to Erasmus, a local high school in Brooklyn. My father wouldn’t have it though. He constantly drilled into me that I could do it, that I was just as good as anyone else. Besides, I felt that since my two older brothers graduated from Stuyvesant, I didn’t want to buck tradition and decided to stick it out.

Looking back now, I could see how someone marginalized by society would be a target for extremist indoctrination

Around halfway through my junior year, something clicked. I channeled my anger into action; I became determined to show I was just as good as “they” were. I forced myself to memorize the chemistry formulas and trig that resulted in phenomenal scores on my Regents exams. But there was a downside. I still felt alienated from my classmates, and alternated between anger and depression, sometimes to the extent that I would be close to tears when I returned home.

Decades later, a similar dynamic repeated itself at Columbia Law School after I retired from the FDNY. I was admitted despite not having a bachelor’s degree, and the students who were mostly White and half my age seemed twice as smart. The experience was buffered by having the support of my wife and son, and a lifetime of meeting the challenges of putting out fires and criminal investigations with the FDNY.

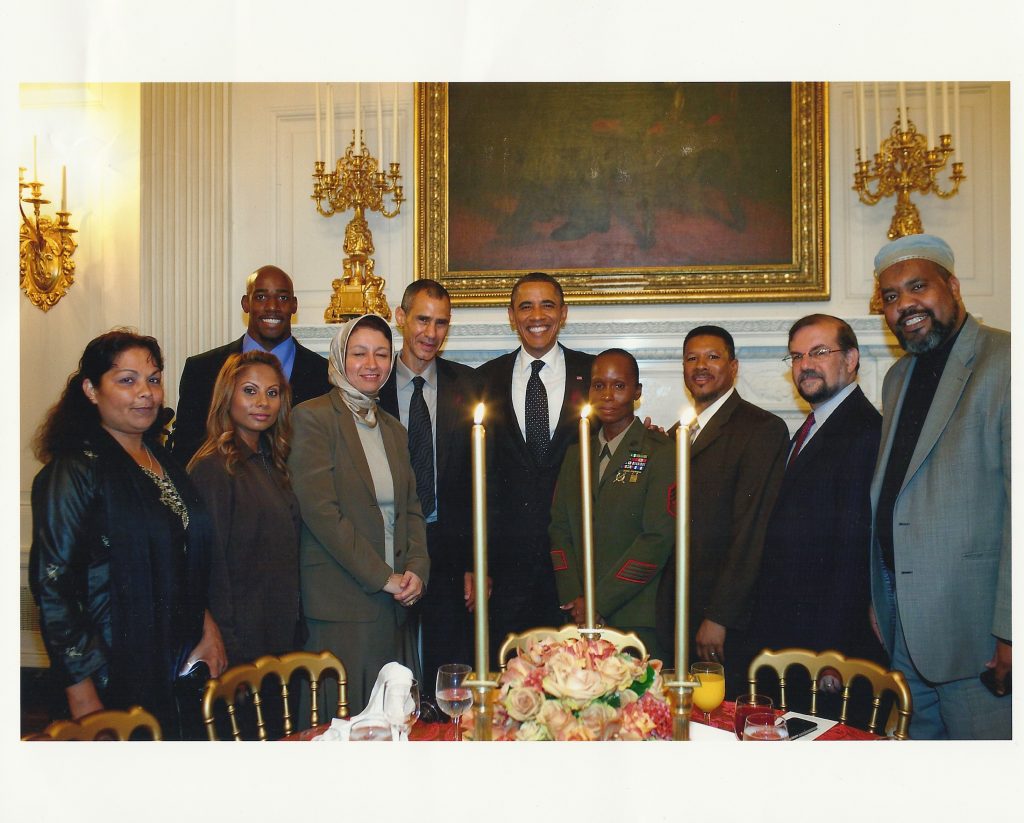

The author (left of Barack Obama) at the 2011 White House Iftar

But there was still a horrendous train ride along with the sense of alienation from classmates that overshadowed my studies. I compensated through brute force, poring over law books back and forth on the train whenever I could find a seat, memorizing recordings of droll legal concepts, and staring at my laptop for hours trying to concoct a single paragraph.

Looking back now, I could see how someone marginalized by society would be a target for extremist indoctrination. As a young man, I learned to channel my frustration in boxing and martial arts, and then to a certain extent in writing. But lacking the support systems of my family, it was not hard for me to imagine the mental state Gilles Deleuze termed ressentiment, the envy fueled from rage and isolation that could be projected outward against those in society who appeared to be enjoying the good life. I contrasted ressentiment with Jean-Francois Lyotard’s differend, which captured the dignitary harms suffered by minority voices rendered mute in the language and ethics of the majority.

Difference and Repetition in the Quran

Over time, my understanding of Islam and identity changed radically. I no longer saw the Quran as immutable or as the word of God, which then opened my eyes to a wealth of meaning. Mahmoud Taha’s Second Message of Islam led the way by harnessing the dialectics of Marx and Hegel. But even in Taha I saw unquestioned premises that Deleuze, cosmology and neuroscience deboned.

The cross-cultural parallelism between tawhid and univocity indicated that Being could only be stated in one sense all the way down. As indicated by the Quran’s metaphor of oceans of ink that could never exhaust Allah’s words, there was no bottom in plumbing the depths of human consciousness.

Above all, I came to see the Prophet as a profound thinker who, as unlettered, could readily mediate his pre-linguistic, pre-individual selves with his ego “I” that operated in real time. Hence the Quran was revealed step by step, or as Deleuze might say, blow by blow. The Quran’s epochal character surfaced not in its purported immutable character that was anything but. Rather, it revealed a Prophet who repeatedly attained to a Being striated by absolute differences in kind.

Apostasy stared me in the face from my old nemesis, the mirror

I came to realize that the import to be taken from Taha and the Prophet was not so much what they said but their internal process, of perpetually making ablution in the waters of forgetfulness to attain the primordial vision with which to see things as they were; to attain to the genesis of the Idea by keeping an ear to the ground with eyes riveted on the furthest horizon. Fidelity to these two giants could only be attained in the depths of one’s thought rather than the length of one’s beard.

I imagined how Allah appeared to the Prophet, with the intellect alif staring across the invisible sea of intensity that informed both the shape and color of the alif and double lam. Implicit to the representation of Allah as a non-gendered “We” was the reciprocal relation between the alif’s will to power and the double lam’s eternal return of difference. From the sea of intensity came the aleatory “Be and it is”; the crystallization of Ideas impregnated by myriad differential relations.

Like the CERN particle accelerator, the Quran exposed itself suffused with the existential currents of difference and repetition, in the repeated retellings of Moses and his individuation with Khidr. Verses that originated in Mecca underscored minoritarian voices, Medinan verses majoritarian. All things perished save the face of the constituting self, and above all, Islam was to be nurtured as an action-oriented faculty against sedentary hierarchies, a “crowned anarchy” of nomadic proportion. Viewed in this light, identity was something to shed, consensual solidarity to be achieved through questioning and testing; predicting and correcting.

Yet within the gravitational pull of solipsism, the elegant insights born of my lines of flight were grounded by a harsh reality — apostasy stared me in the face from my old nemesis, the mirror. The sobering thoughts came in rapid succession: So long as we lack the capacity to enact our highest values by serving humanity and to resurrect innocents with our tears, until we view the visage before us as the “Other” of our inmost self and cherish the genesis of differences between us as jewels lighting the night sky, and up to when we bathe in the River Styx to see through the eyes of the Prophets and swim in the Paradise of immanence where the past is gone and the future is now, we are doomed to the rage incited by pointless political identities devoid of meaning.

*Image: A bodega in Brooklyn. Flickr/Shawn Hoke

This piece appears in our Winter 2016/2017 print issue.

This piece appears in our Winter 2016/2017 print issue.