This is the first Ramadan since the 2016 Pulse nightclub massacre in Orlando. I remember watching TV on that night during Ramadan, and feeling like I was punched in the gut when Omar Mateen called 911 to claim his allegiance to ISIS.

Going beyond the condemnations of the attack, American Muslims, including me, showed up at Pride events in the days that followed. I attended a Pride vigil along with a group of my fellow Muslim community members. We carried placards announcing our love for “them,” and felt ashamed that one of “ours” had killed “their” people. We were humbled by how readily those at the vigil accepted our presence. Men with nail polish and women in buzz cuts embraced us, a group of Muslims, some in head scarves, almost all Brown. I feared that if, instead of forgiving us so readily and unconditionally, they asked us about how we were taking care of our own queer Muslims, what would have been our response?

When I returned home that night, having witnessed the Muslim community’s outpouring of compassion for the LGBTQ community at the vigil, I fully expected to wake up to a revolution in the mosque. I didn’t know what that revolution would look like. Would mothers at the mosque no longer feel like they had to privately message me to ask if their gay child was “normal,” or if I could “cure” their son? Would gay Muslims no longer feel compelled to hide their identities or risk being excluded, pushed into arranged marriages or even shamed? Would this rush of anguish break down the usual pretense? Would we embrace each other in a rush of tears and compassion, and queer people would come out en masse, because this was a time like no other?

Vigil in Minnesota for Orlando victims. >Flickr/Fibonacci Blue

But there was no revolution, and I heard no proclamations at the pulpit to counter homophobia. Instead, there were denunciations of an attack by a deranged, secretly gay man who had misappropriated the religion. We had neatly compartmentalized the problem. One prominent American Islamic thought leader, Yasir Qadhi, summed up that mindset well in a Facebook post where he claimed, “[Mateen] was mental, plain and simple. Islam’s stance on homosexuality is IRRELEVANT to this massacre, period.”

Queer American Muslims remained under-represented in the national religious discourse, even in their time of unprecedented collective grief. They were shoved further into the closet by their religious leadership. American Muslim parents, many of whom are immigrants from countries that criminalize homosexuality, often don’t find a community to turn to when their child comes out. Many of them are unaware of how their child’s life can depend on their acceptance and support. The occasional transgender person who is bold enough to ask for accommodation in a gender-segregated communal prayer can be discouraged from attending, if not ridiculed outright, their quest for a spiritual journey met with sneers.

For contemporary American Muslim imams, most educated in the puritanical traditions of seminaries abroad, sex is a taboo topic. Homosexuality may as well be a Martian construct to these imams. While gender fluidity is a firmly entrenched phenomenon in many Muslim majority countries, LGBTQ participation in religious life is fraught with obstacles. American mosques, with their clear segregation of gender, are not easy either for gender non-conforming people.

Homophobia, however, is not exclusive to Muslims in America. American LGBTQ children and adolescents are mercilessly targeted for bullying, and are unsurprisingly at higher risk of suicidal behavior. The recent spate of “bathroom laws,” and associated transphobic rhetoric in conservative Christian circles, has laid bare the pervasiveness of homophobia in America

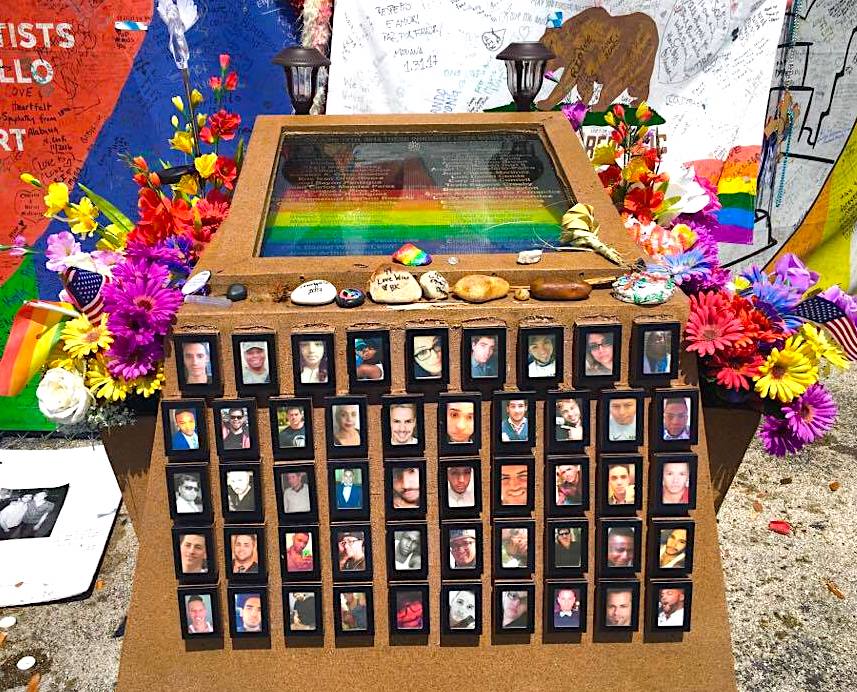

The site of the memorial, one year later. >Photo via Islamic Monthly columnist Laine Munir

Since September 11, 2001, American Muslim communities have had to mature quickly under intense scrutiny. American society and law enforcement have relentlessly, and often unfairly, interpreted what goes on inside mosques through the lens of terrorism. In a climate of intense Islamophobia, American mosques avoid fiery foreign-born speakers preaching warmongering in the name of jihad, or vocal congregants with anti-American sentiments.

Most scrutiny over how Muslims treat their LGBTQ coreligionists has come at the hands of established Islamophobes who tend to engage in a warfare of sorts against everything Muslim, taking away from legitimacy of the discourse. It was perhaps reflective of the fear of being co-opted by Islamophobes that in the days after the Orlando massacre, the Muslim Alliance for Sexual and Gender Diversity responded with a statement: “This tragedy cannot be neatly categorized as a fight between the LGBTQ community and the Muslim community. As LGBTQ Muslims, we know that there are many of us who are living at the intersections of different communities and identities, and we recognize the complexity of these experiences.”

It shouldn’t have taken a mass shooting for us to have shown solidarity with gay people, but it did, and still, little changed afterward. Our mosques, at least the ones I have been involved with, did not become the wellsprings of support that queer Muslims could rely upon. There was no collective self examination regarding how Muslims plan to support queer members of our own communities who were doubly hurt by a Muslim man’s attack on gay people. Even in that time of grief, there were no warm embraces of gender non-conforming congregants in the lobby, and I didn’t see any mosques put up rainbow signs in their entrances.

While the revolution has had to wait, attitudes of American Muslims have been slowly changing. Among the Muslims surveyed in a 2017 Institute for Social Policy and Understanding poll, 1 in 10 did not identify as heterosexual. As one of the most diverse faith communities in the U.S., and with its embrace of progressive values demonstrated in surveys, the American Muslim community may be at the brink of broader change.

*Image: The site of the memorial, one year later. >Photo via Islamic Monthly columnist Laine Munir.