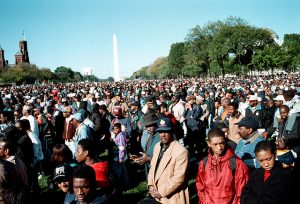

October 16 will be the 18-year anniversary of the Million Man March. Although forgotten by many, this event marked a critical moment in American history. Not since the March on Washington in 1963 had the nation’s capitol witnessed such a powerful display of mass unity and purpose among the Black American community. Led by the Nation of Islam, the rally also brought together an impressive group of leaders and freedom fighters including Minister Louis Farrakhan, Dr. Betty Shabazz, Martin Luther King III, Rosa Parks, Maya Angelou, and Dr. Cornell West. The March focused on the plight of black American males emphasizing the theme of atonement. It also covered a range of social and economic issues relevant to urban America. Reflecting a tradition of black empowerment, the March speakers promoted unity among American black males as a source of community strength and development. They called for men to challenge the violence in their communities and fulfill their roles as husbands, fathers, and leaders.

Today, very few people commemorate this important historical event. Yet I believe that the universal message of the March remains a critical one for black America, for Muslim America, and for all of America. Indeed, while the call of the March was to black American men, in particular, the rally’s purpose could easily apply to any community. And the rally itself was only a first step. The real mission was to set in motion a series of local efforts that could transform the conditions of oppressed communities throughout the United States through a reformation of men, in particular. This did not mean that women had any less a role to play. Nor did it suggest that women had to sit around and wait for men to make all the necessary changes. Instead, the March took a step towards recognizing that a problem existed among men and that solving it required an emphasis on the condition of men in their communities.

In commemoration of the March, and of the spirit of critical self-improvement it promoted, I want to revisit the question of men. Specifically, I want to focus on the question of Muslim men. As a Muslim male myself, I think there are several good reasons for examining some of the issues facing Muslim communities today that has something to do with men. One of those issues concerns unity. Thus in the remainder of this article, I will offer a few short thoughts about the lack of unity in our communities that, like the call of the Million Man March, might serve to catalyze local efforts to improve our communities and compel a critical evaluation of what it means to be a Muslim man.

It’s not uncommon today to hear that Muslim men are obstacles to the experience of unity our mosques are supposed to provide. Unity can mean many things: theological, ethnic, and/or political. In this case, however, I want to focus on the more basic unity between Muslim men and women. Having lived as a Muslim for the last 16 years, I’ve been to plenty of mosques and met with plenty of Muslims. From these encounters, I’ve heard a similar complaint about the lack of gender unity in the mosques. Specifically, many Muslims have expressed their frustrations with the physical and spiritual barriers that exist between women and men. From limits on leadership roles to the unequal facilities of the mosque, inequality and separation seem to be serious issue affecting many within our communities.

When the Million Man March called for men to step up and take responsibility for the quality of their communities, it affirmed two important points: men are part of the problem and men have to be part of the solution. The inequalities between Muslim men and women mentioned above seem to fit well within this framework. In short, the lack of equality between Muslim men and women in their communities suggests that Muslim men are part of the problem and thus need to be part of the solution. First of all, Muslim men are the overwhelming recipients of most of the benefits of their communities. Our facilities (prayer space, bathrooms, etc.) are often much better than the facilities offered to women. In addition, the leadership of our mosques is often overpopulated by the men of our communities. This means that men get to decide on the future of the community with limited input from women.

If men are benefiting from inequality, then men are responsible for making things equal. Taking responsibility as Muslim men means, first, acknowledging that we are beneficiaries. That means critically examining the conditions in our community and acknowledging where and how men are getting the better deal. This may be challenging since some of the benefits are normalized through ideologies of sexism. The idea that men are better suited to be leaders and thus should hold executive positions in our mosques, for example, is classic sexist legitimization. The most cursory look at the history of human leadership suggests anything but the neat dichotomy assumed in the proposition that “men are natural leaders.” As men, we have to be willing to see through the normal operations of inequality and question our position.

Taking responsibility for the inequalities also means challenging the unfair entitlement we’ve inherited as men and ensuring that women get their fair share of all that makes up our communities. Consider the lack of adequate prayer space for women in mosques. While it may be true that, in some communities, more men visit the mosque for daily prayers, that doesn’t mean that women deserve anything less than a dignifying space for their prayers. In a mosque I attended for several years, the men’s prayer space was always the priority. Spill over during Friday prayers and Eid prayers seemed to always push the women farther back into the mosque. Sometimes, it put them in a crowded hallway. The inequality was also visible in the bathroom facilities. The men’s bathroom was remodeled for quite some time before anything was done for the women’s.

These may seem like trivial matters in the grand scheme of community. But they’re an important piece of a mosaic of inequality that many Muslims feel on a daily basis. From the emphasis on “brothers” in the Friday lecture to the often imposed segregation of women from men in communal activities like iftar, the operations of the community seem to favor men’s needs and perspectives. But these are not benefits nor are they entitlements. And men experience these inequalities as benefits only because they fail to see women’s needs and perspectives as equal to those of their own. In short, they fail to understand the meaning of unity.

Of course, not all men are responsible for creating these inequalities. Many of us have little say in the structure of our mosques and communities and are frustrated by the inequalities between women and men. But the fact that we didn’t create these inequalities doesn’t mean we aren’t responsible for changing them. After all, passively enjoying the benefits of inequality makes us responsible for reproducing them. Thus, like the men at the Million Man March, we have a choice. We can look critically at our communities and be the force of change or we can continue to build on the systems oppression that not only limit the meaning of unity in our communities but also limit its future. Remember that the Million Man March focused on the theme of atonement. Atonement is about reparations for wrongs or injuries committed against others and God. Rectifying the inequalities in our community can thus begin with this very idea: acknowledging and repairing the system that made our communities unequal. Doing so will be an important step in fulfilling our roles as men, which is defined as much by what we do as what we don’t do.